Introspective: The echoes of old bones

Tonight I had a profoundly emotional experience. Earlier today while in a coffee shop I researched the history of this area in lieu of sightseeing. Generally I’m far more interested in the sort of natural sights or functional constructions rather than tourist oriented attractions.

After finishing up blogging for the day I decided to take a ride around the town, and after aimlessly wandering I decided it would be foolish if I didn’t go and see the local attraction: The giant buffalo statue.

I never made it. My trek took me through “Frontier town” which immediately struck me as a kitschy attempt at creating a commercialized facsimile of a late 1800’s frontier town. I breezed through the “town” towards a parking lot of the North American Buffalo Discovery Center (aka National Buffalo Museum), where they advertised a live herd.

I peered across the parking lot to see a small grouping of bison, and a wave of emotion hit me. Here between the sewage treatment plant and the highway was the best we could muster for a herd of perhaps 15 bison, survivors of a project of mass extermination based on convenience and domination.

I rode away feeling deeply ashamed, angry and hopeless. I know the people that work there are probably genuinely doing the best with what they have, and have the best intentions, but this is a national and historical travesty to me, and we are set to repeat the same willful destruction through the defunding and removal of protections on our national parks and lands.

I’m still numb. I’ve seen an American bison two feet outside of my car window in Yellowstone as it wandered through a parking lot. I saw others from afar while biking through the park.

I don’t have much else to say except for the article I worked on earlier today to give the context to my feelings.

American Erasure: An abbreviated history of the North Dakota Prairie

In the 19th century, as settlers surged across the Great Plains, lands like those surrounding Jamestown, North Dakota were rebranded in the national imagination. Where Indigenous peoples had lived, hunted, traded, and prayed for generations, settlers and policymakers saw only “open land”—unused, unclaimed, and ready for “development.” But that development required more than plows and railroads. It required the removal of the people already there.

Tribes such as the Dakota, Lakota, Yanktonai, and Cheyenne had called this region home for centuries. They had mapped its rivers, buried their dead on its hills, and followed the migrations of the buffalo across its prairies. Treaties like those signed at Fort Laramie in 1851 and 1868 had promised them sovereign use of vast swaths of territory. But these promises were broken whenever they became inconvenient—whether for railroad right-of-way, settler farms, or simply to fulfill the ideology of Manifest Destiny.

This was not just a military conquest. It was a cultural one. And two of the most effective tools of that conquest were the deliberate extermination of the buffalo and the forcible reeducation of Indigenous children.

The Death of the Buffalo:

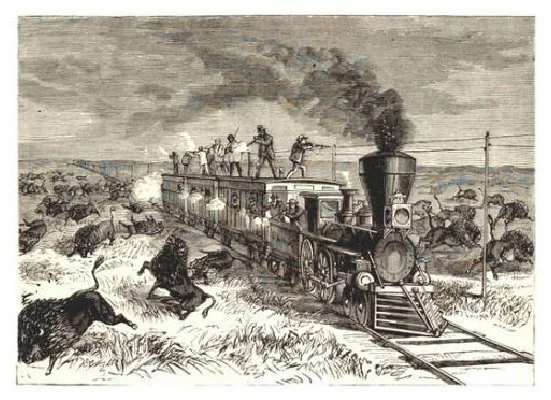

The American bison was more than a source of meat. It was the beating heart of Plains cultures—providing clothing, tools, shelter, ceremony, and above all, independence. As long as the herds roamed, tribes could resist full dependency on the U.S. government. Which is why U.S. policy and military strategy deliberately supported their annihilation.

Railroads carried in waves of hide hunters. Carcasses were stripped and left to rot. Bleaching bones became the first cash crop of settlers, sold as fertilizer. The herds, once numbering in the tens of millions, were reduced to near extinction in less than two decades. General William Tecumseh Sherman was tasked with using the scorched earth tactics that had been used in his March to the sea during the civil war. He employed subordinates and commanded a troop of 14,000 men in a campaign against the plains tribes. The tactics were described plainly: “Kill every buffalo you can! Every buffalo dead is an Indian gone.” - Col. Dodge

From 1867 over the next three years to 1889 there was a bonanza on the massive herds of bison in the west, explicitly promoted to starve out the plains tribes.

“These men have done more in the last two years, and will do more in the next year, to settle the vexed Indian question, than the entire regular army has done in the last forty years. They are destroying the Indians’ commissary. And it is a well known fact that an army losing its base of supplies is placed at a great disadvantage. Send them powder and lead, if you will; but for a lasting peace, let them kill, skin and sell until the buffaloes are exterminated. Then your prairies can be covered with speckled cattle.” - Gen. Sheridan

Stories tell of entire trains full of men with .50 calibre rifles, thousands strong firing from the roof and windows of trains moving slowly past herds, leaving a sea of rotting corpses. In this three year period it’s estimated that 30 million bison were killed. The sight a ghastly armageddon to the tribes of the plains. Eventually Bison were hunted to the brink of extinction, forcing plains tribes to fully surrender or face annihilation themselves.

Sheridan was right. The disappearance of the buffalo meant the collapse of a world. It was no accident—it was ecological warfare, and it succeeded.

Boarding Schools: Cultural Genocide

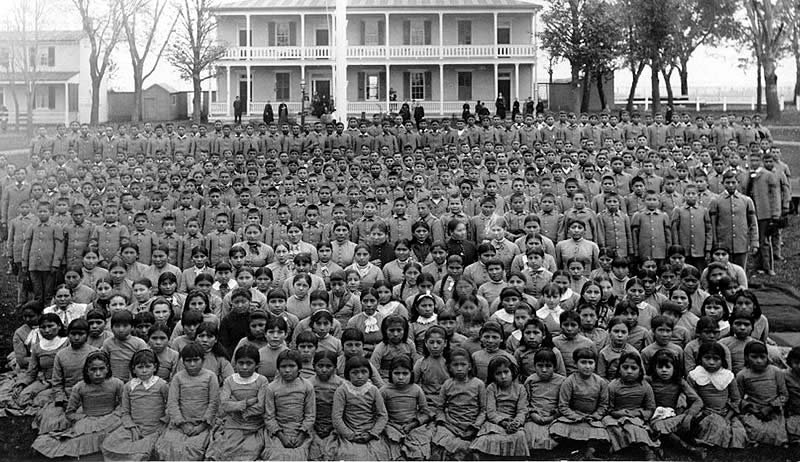

Breaking Indigenous resistance wasn’t just about killing food sources. It was also about destroying identity. From the 1870s into the 20th century, the U.S. operated a vast system of Indian boarding schools, where Native children were taken—often by force—from their families and communities to be “civilized.”

Their hair was cut. Their languages forbidden. Their names replaced. At places like Fort Totten Indian School in North Dakota and Carlisle in Pennsylvania, children were beaten for speaking their own languages, subjected to malnutrition and forced labor, and in far too many cases, raped or killed. Many never came home. Thousands are now known to have died at these institutions, buried in unmarked graves under a system of recordkeeping that treated them as less than human.

The goal of the boarding schools was not education—it was cultural genocide. Captain Richard Pratt, founder of Carlisle, said it plainly: “Kill the Indian, and save the man.” These schools were an extension of the same logic that cleared the land: erase the culture so the land can be claimed uncontested.

The Great Irony:

Today, Jamestown is known proudly as “Buffalo City.” A giant 60-ton concrete buffalo looms over the valley. Local sports teams are named the Buffaloes. The town hosts a bison museum and maintains a living herd nearby.

This presents a deep irony—if not an indictment. The buffalo, once hunted to near extinction to erase Indigenous independence, has been rebranded as a mascot and monument by the descendants of those who displaced its original keepers. The symbol of survival is now a tourism asset. The creature that was sacred was made into cement, then turned into a logo.

This irony is not unique to Jamestown. Across North America, settler societies have often adopted the imagery of the cultures they destroyed, wearing their feathers, using their animals, claiming their legends—without acknowledging the trauma behind them.

Reckoning with history:

Above is an image that deeply moves me every time I see it. It is a picture of tribal representative George Gillette openly weeping at the signing over of 154,000 acres of land for the creation of the Garrison dam reservoir north of Bismark. Signed over in 1948 this represented yet another transgression upon the indigenous people of the upper midwest.

None of this is to say that modern residents of places like Jamestown are guilty of their ancestors’ actions. But history does not need our guilt—it needs our honesty. The prairie wasn’t empty. The buffalo didn’t vanish by chance. The children in boarding schools didn’t just get an education. These were systemic tools to clear the way for capitalism, settlement, and a new vision of the land that required silence from those who lived on it before.

To remember the truth is not to hate the present. It is to recognize that the foundations of our communities were often laid atop erasure—and that healing begins by naming that truth out loud.

I once felt the immense gravity and scar left of the land by the trail of tears in Golconda, Illinois. We must not allow these wounds to continue to be perpetrated.

As I left the parking area this evening I queued up the song “Beautiful things” by Gungor as a kind of hopeful cry into the void that we could be and do better.

I don’t know. I’m emotionally spent…